“I am not seeking for my work to be authentic to me — but rather, I want it to be authentic to the idea of that piece. Which is similar, but slightly different.”

Fraz Ireland

Fraz Ireland is a composer and conceptual artist currently based in Manchester, UK. Since graduating from the Royal Northern College of Music / University of Manchester joint course, Fraz’s projects have included: an interactive soundscape as the composer-in-residence for a conference, a brass fanfare imitating the sounds of traffic and various warning sounds that was performed in St Paul’s Cathedral, and a choose-your-own-adventure style piano piece with choose-your-own-adventure style program notes as part of Psappha’s ‘Composing For…’ scheme. Fraz was a Britten-Pears Young Artist in 2020 and has worked with ensembles including the Riot Ensemble, The Tallis Scholars, and the Ligeti Quartet. Fraz spoke to PRXLUDES about their use of text, titles, and programme notes, the concert experience, their relationship to the score, musical perception, and more…

–

Zyggy/PRXLUDES: Hi Fraz! Thanks so much for chatting with me. What have you been up to recently, creatively?

Fraz Ireland: Recently, I’ve been having lots of smaller things, and lots of intermittent ideas, rather than specifically working on “a” project right at the moment. I kind of am, in some ways, but they’re all my own things that I want to do. It’s difficult going from periods of being really busy and working on several things at once, to having a “gap” [where] I’m not working towards a concert. That said, I am working towards [a] concert called ‘Music for the Changing Hour’ — that’s what I’m thinking about at the moment. It’s been going just under two years now — there’s been four concerts — but I’m looking to take it in a slightly different direction, building on some of the things I’ve been working on recently.

I remember ‘Music for the Changing Hour’ — it was a blast being involved last year! What kinds of ideas are influencing this new direction for the concert series?

[For] the last two years, I’ve invited other people to submit stuff, and I’ve put that together and spoken between tracks. However, I’ve not written anything for it myself… and I want to do that. I think that would be fun.

I was invited to perform as part of FLUFF, which is a queer electronica night in Manchester which happens every few months (curated by Industries and Norrisette). I decided to make a 20 minute long set that’s like a guided power nap. I was inspired by guided meditations, and power naps, because… You know Spotify Wrapped?

Of course — how does that fit into the piece?

My, like, top listened to song on Spotify Wrapped was a 20 minute guided power nap. -laughs- I think that was the first year covid happened. I would do a 20 minute power nap, at some point, every single day. But I listened to this one specific track, which I was really drawn to, because it kind of wasn’t particularly relaxing… It was just a bit weird. I found it quite interesting, creatively — the idea of being sort of asleep, but being guided through being asleep through music. So I started at that, and made this track that was a 20 minute power nap… Except it was also designed for this queer night! It wasn’t really soporific — it’s more about the idea of taking an audience through a journey. Which I guess a lot of my work is about.

So [the piece] starts, and I’m introducing people to this meditative space… An exploration into creating spaces an audience can inhabit. It does a lot of silly things: when I was researching sleep, and power naps, one of the things I had found was a study that was reported in the New Scientist. [In] the study, they got a bunch of students to watch a video about crabs, and then half of them had to sleep, and then they had a test on [the] topic… and the ones who’d been asleep could recall more about crabs. So then, throughout my guided nap, I interspersed facts about crabs. There’s this YouTube video I found, that’s some guy talking about [a] video that he saw about a crab, at the bottom of the ocean, trying to eat a bubble of methane. I’ve got this guy talking about the crab, me talking about other facts… Just an overload of information and sounds.

Does the piece have more elements that relate directly to aspects of guided meditation?

Yeah. You know how sometimes, when you’re doing a guided meditation, and it’s like “breathe in, breathe out…” — and it’s all about taking a deep breath? So I’ve got a whole section where it’s about “breathe in, breathe out”, and it mashes up with the hokey cokey. -laughs-

I was on this tour [over the summer], and part of that was that we went to different cities, and I would do bits of this performance — but with another eight musicians, who were also doing their own performances. We ended up making this one hour set of all of our different things. The crucial thing about that is [that] over about two months, I was approaching this one set again and again, and shortening it, taking different bits of it, refining it. It’s not something we normally have the luxury to do — to come back, and come back again, and change it and try it out in different ways. Every time I have done something like that — which is super rare — it’s gone really well.

I completely understand — it’s like we’re always working to one specific premiere, or performance, and revisions seem to get lost in that. Have there been any circumstances where you’ve been able to revise a piece in a large-scale, or orchestral, setting?

The one other time that happened to me was when I was writing this orchestral piece during lockdowns. It was meant to get performed in October, and then it got to September, and they were like “we’ve got to cancel this concert, it’s gonna be in December”, and I was like “okay cool, can I revise it?” — and it got to December, and they were like “we’ve got to cancel it, it’s gonna be in June”… -laughs- So I got to revise this piece twice, which was amazing. Having revised it twice — it was so much better then than it would have been if I’d just had it performed in October.

You put different parts of your authentic self in things at different times, right?

Yeah. It’s interesting, the idea of authenticity, as well. Because I almost think I am not seeking for my work to be authentic to me — but rather, I want it to be authentic to the idea of that piece. Which is similar, but slightly different. With this orchestral piece: at each point I was writing it, it was authentic to what I was thinking about at the time, but the third revision was the best realisation of the original concept. Having had enough time to be thought about lots, and over again, [and] be incubated, really. Sometimes pieces are performed before they’ve hatched into chickens. -laughs-

So, now I have to ask; what was the concept of the piece?

It’s called ‘Three Men Discuss Beethoven’s 4th Symphony’. I was asked to write a piece that could be performed alongside Beethoven’s 4th Symphony, and comment on it in some way. I thought about this for a while; it’s a really interesting thing to be asked to do. At this point in the beginning, I was like “I’m gonna think about what it means to comment on another piece, and not at all about Beethoven because I just don’t care.” -laughs- So I got to this point where: isn’t it interesting the way that we talk about music, and the way that we think about music with other people, the way we comment on stuff?

This was written after the first lockdowns of 2020, and I was thinking about the things that we’re missing from going to live concerts. I still think, quite strongly, that one of the most important things about going to live concerts is the conversations you have after it, and before it, and around it. The little interpersonal bits. Obviously, the music is nice, and it’s nice to be involved in it, but for me, the big / biggest thing that was missing was being able to overhear other people afterwards be like “oh, that bassoonist messed up…” — talk about the things they liked, or didn’t like. So that’s where I went with this piece: I’m gonna get three people to talk about what they think about Beethoven, and Beethoven’s 4th Symphony, and then I’m gonna write a piece about their conversation. In the whole process, I never listened to Beethoven’s 4th Symphony; I decided not to listen to it until the concert.

I love that idea: writing a piece that very much draws on a piece that you haven’t heard before.

I probably listened to it in the past, but I don’t have a good enough memory for pieces of music to be able to recall exactly what it’s like. But I was able to quote the piece; because the people in the conversation sung quotations of it.

So the concept of it was the way that we talk about music — it’s distant and different from the music, and kind of creates its own pieces. It’s loosely a trajectory, which starts off very close to Beethoven, only based on the quotations, and none of “my own” music (or at least the bits that are me are my version of Beethoven) and gets gradually further away from him, and becomes more ‘me’… So it was also a little study on how to sideline Beethoven a bit, by making a comment not about Beethoven, but about commenting, and just happening to use Beethoven to do so.

These people were a trumpet player, and trombonist, and a [violist]. There’s no trombone in the piece — so the trombonist only knew it as a conductor — and the trumpet player knew it as a trumpet player, so he came out with this opinion that the second movement is a bit shit. They were all talking about the bits that they don’t think worked that well in the Beethoven. Which meant that — [as] my piece was performed directly before the Beethoven — I had this piece, and everyone in the audience was hearing about how the second movement falls a bit flat… And then the conductor — who was Sir Mark Elder — walks onstage and is like “actually, the second movement is really nice”… -laughs- Which I found excellent, because it’s so rare that when you’re performing Beethoven, you can frame it in a way that makes people listen to it differently – and even defend it!

What major elements ended up changing in your revisions of the piece?

The bit that I added on after revising it was a full minute at the end with timpani glissandi and string stabs — [but] because the conversation ends with them talking about how happy the piece is, I start quoting “if you’re happy and you know it, clap your hands”. -laughs- Of course, the audience gives applause at the end. I kind of think the last note of the piece is the audience clapping… Completing the prophecy of clapping your hands when you’re happy. That wouldn’t have happened at all if I hadn’t had the opportunity to revise it.

Of course — it feels like what you’ve managed to do with these revisions is find the points of refutation, and then incorporate them.

Yeah, absolutely. I definitely have other pieces where they could do with revising, and where if I explain the piece, I feel like I need to [add] an extra paragraph being like “this is what I’d do next to make it watertight.” Not that everything has to be watertight — but when there is a concept behind something, if you’ve done it 80% of the way and not done that last bit, it leaves a bit of a question. But, you can absolutely — and should — not necessarily follow every single thing to their absolute conclusion. If composing was just about taking things to their extreme, that just becomes more [like] science; there’s no instinct. I think instinct is really important. In some ways — with the Beethoven piece — I don’t take it to its logical conclusion, I don’t take it to the exact opposite of Beethoven. It’s about sitting with pieces for enough time. But no-one has [the] luxury to do that with everything. There should be more opportunities and schemes for taking along a piece you’ve already done, and rewriting it, revising it… adding to it.

One thing I love about your work is the way it negotiates with the concert experience in such depth — what relationship do you have with elements such as titles, programme notes, and non-standard notation?

Something that I’ve been quite interested in for about three, four years, is the framing of work: how we’re titling, and giving programme notes to things, in a way that invites the audience and the performer. How we’re using paratext to invite the audience to be in a certain headspace, or enter the piece in a certain way. Quite often, the audience and the performer are very intermingled roles; the performer is an audience of something, and the audience is the performer of some things.

About five years ago, I started thinking about this with a piece where I wrote a very simple melody, and sent it to loads of different violinists with four or five different titles at the top. I asked them to play it, record it, and send it back to me; then I layered it up, gave the piece a whole new title, and put a live violinist there (small plug for Katherine Stonham, who ever since we met about 10 years has willingly tried out, performed, and discussed so many pieces that I’ve put on music stands in front of her!) None of the titles had any relationship to the music, but what I was exploring was how people found their own connections between the title, and the music that was there. The final title, in the concert, was ‘The death of violin and how to avoid it’. I had audience members coming up to me and asking about the title. I remember someone was like “that made me think about the shape of the piece, and how it has a dying moment and a resolution…” — I listened to a few people tell me how the title connected to the material, for them. None of it was anything I had thought about, or was trying to do. But it really emphasises the fact that: if you put two things next to each other, we will draw connections between them.

That’s really interesting to think about — how a piece’s title simultaneously means nothing and everything at the same time.

I remember the very first National Youth Orchestra course I went on, when I was 15. We did this exercise where each of us would write a melody, and an accompaniment — they were completely separate — and we put them all into a hat and picked out two at random, and played them next to each other. Every single one of these pieces worked. And that really changed the idea of two different bits of material going next to each other — how we think about foreground and background, the idea of something ‘working’. It’s something I always think about, because it demonstrates that you can put two things next to each other, and no matter how they’ve been conceived, they are going to connect to each other, and people are going to connect them.

To go back to where I started — titles and programme notes — I wasn’t exploring it scientifically. I was just jumping into it, really; take your shoes off and play in the sand for a few minutes… or days… or years. That was the vibe. So I stepped into this barefoot, as it were, and tried loads of different titles and programme notes.

One of my favourite pieces that I’ve done is called ‘The Lost Supper’ — which is an imaginary ASMR experience, performance art piece. There was a big tech change between the previous piece and my piece, because I needed six microphones and a long table, and someone was like “can you filibuster?” So I just stood up and spent ten minutes chatting, setting the scene, talking about the restaurant that we were all in, the creatures of the carpet and the way it’s looking at your toes… -laughs-

How did you know exactly the way you wanted to set the scene?

I had a few notes. But I knew the kind of vibe I wanted to create, which was the idea that everyone in that room was in a weird restaurant — weird in an almost magical way. There’s mysteries everywhere. The head chef was born in a water bath, but it was cucumber soup, and to this day he’s never made cucumber soup because it’s [of] spiritual significance to him. Loads of ridiculous imagery, stupid and strange and… fun. That creates a space where listening to the rest of the restaurant piece makes sense: the rest of the piece [consists of] eight people and six chairs, behind this long table. They sit down, and open their menus, and order food, and then the food comes and they eat — they have to try and make the mouth sounds that the food they ordered would make. The piece was really about how I am giving programme notes for it.

How did you go about scoring the piece?

The score for this piece is just a book of menus. You know how if you go to a restaurant, they’ll have a three course saver menu, a kids menu, things like that? It kind of has that, except the themes are [different]. One of the menus is food that is shapes, so there’s like a box jellyfish, those Kellogg’s square bars, starfish; there’s fast food, which is just the ten fastest animals in the world. But the very front page of [the score] is a page of writing setting the scene, and giving the ethos of the restaurant, in the way that sometimes restaurants do — “if you’re not having a nice meal, you’ll be asked to leave”… It’s about creating a mythology around the work, and thinking about a piece as the universe that it’s creating, the world that it’s existing in.

Psychologically speaking — what kind of relationship do you see this approach building with your performers, as well as their relationship with the score?

Sometimes, composers just see their score as a way to make their performers make the sounds that are in the composer’s head. I can understand that, and I have written pieces like that; but recently, I’ve been so much more interested in using the score as a way to invite performers to respond to something that I’m giving them, in order to create sounds that maybe I’ve not entirely preconceived, that then the audience will listen to, that maybe invites the audience to engage with them in a certain way. It depends from piece to piece, to what level these things are happening; but all of the things I’m giving to a performer, I want to [give] really carefully.

An example I was thinking about was: when you’re a kid, and you’re inviting someone to a birthday party, you make that invitation the same theme as the birthday party. Like, “come to my fairy party”, and the invitation is a pink flower with glitter on it. Or Halloween — lots of people are interested in Halloween at the moment. Or weddings… those are parties that grown ups have. -laughs- If you’re inviting people to stuff, you’re inviting them to join in the world you want your party to inhabit. That is the approach I take to presenting performers with a score. That’s not to say that it’s a childish approach — and it’s not even always different from giving them sheet music with dots and lines — but I like to really think about why the dots and lines are like that. What is it about those dots and lines that’s not just “this is some sheet music, you’ll play it and it’ll be the right character because I put the right thing on the page”? It’s more: here’s a piece of paper that, if you look at it, you’ll understand that kind of vibe that I want. Sometimes that’s as simple as writing big, strident music, and making the width of the lines slightly thicker.

For example, my orchestral piece ‘…and mother said to the child “darling, you must remember to name that pet fish before it dies” and the child did as it was told’ — in that, there are bits in some of those parts which have really in-depth instructions. They’re kind of like conversations with the performer. In the piano part, the only thing the pianist plays is one chord, again and again, for about two minutes. It’s got about a paragraph and a half of description of how to play this chord. In doing that, I’m thinking about what the pianist is thinking; it’s not that I necessarily want the pianist to play it in the manner described in the paragraph, but I want the pianist to feel like I’m having a conversation with them about [it]. They’d perhaps be a bit irritated about being given this piece of paper that’s got this one chord, and [a] stupidly long paragraph describing this — “unsupervised child smacking a recently captured fish against gritty harbourside concrete…” — it’s quite a wanky thing to do as a composer, but if the pianist is playing this chord with a bit of anger, and frustration, at me — that’s the vibe that I want.

I get it. Having some sort of shared felt experience between composer and performer — whatever form that relationship ends up taking.

I did another piece — at the time, I credited it as “my most queer piece” — and it’s interesting in how we were talking about authenticity, in that actually, that piece was very vulnerable. It had a lot of me in it, in ways that other pieces of mind hadn’t. It came about at the same time as my website — and it’s based on the most vulnerable bit of my website, which is not vulnerable for me, but vulnerable for the audience. At that point, the website had a survey on it, [which] starts by asking innocuous questions, and gradually asks you more “searching” questions — questions inspired by equal opportunities forms, and forms your doctor would send out, ADHD questionnaires… But in a kind of power move, I — the person who made the website — don’t give options for you to answer them properly. It’ll be a big long question that can’t be answered in one word, and you’ll have “yes” and “no”. And you can’t even submit the survey. So I never see it, but the idea is that the audience will click all of their answers, and get to the end, and: maybe they’ll be pissed off with me, or maybe they’ll have found out something new about themselves, or thought about something in a slightly different way. That’s why I think that’s a vulnerable part of the website.

How does this survey then relate to the piece you’ve written?

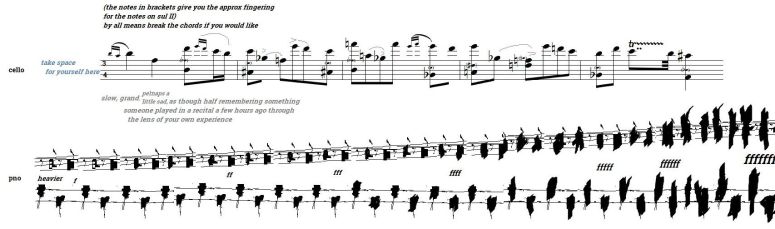

This piece that I wrote — which is called ‘Some questions’ — is almost a flip of that. It’s for singer, cello, piano, and clarinet, which was very nicely workshopped by the Riot Ensemble at RNCM. I put a lot of my own feelings into the score. The score is about fourteen pages of notation. It’s all landscape — landscape scores are really unhelpful, because music stands aren’t landscape. The score itself was created in different software; I used Sibelius mostly, but I would screenshot a bit of it and put it into Photoshop. Loads of it was taken into Microsoft Paint… I’ve done a video on my website where I’m talking about what Paint is. -laughs- I was thinking about how that piece has its own world that it exists is. Each page of [the score] is different. It’s got this recurring train drawing, which is very personal because it’s based on a sketch that I repeatedly drew when I was in secondary school. One page is just washy colours and little bits of poetry-like writing. I was thinking a lot about how things are written down, and the importance of handwriting. I think handwriting is great. I don’t mean that in the sense of “handwriting music”; I mean it in the sense of capturing what handwriting is. Putting your own identity into something.

Do you find that creating notation with these different pieces of software helps circumvent the limits of using software, or particular mediums?

As composers, we know the way that software limits us. It’s such a common thing, to be in a masterclass or workshop, and someone to present a score and be like “yeah, I don’t know how to do that in Sibelius.” This isn’t me doing a rant on which software we should be using, but: it’s really fiddly to make a flared crescendo on Sibelius. I can’t think of that many times where I’ve seen scores by my peers that have flared crescendos in. However, in Dorico, it’s super easy. The crescendo is a neat example of that, but it’s really important for us as artists to think: how are we being limited? Which of those things are things we can avoid, and which are things that we’ve not even noticed?

A great example of that is your incredibly uniquely designed composer website — how did that come about?

I needed a website. For a bit of time, I had two websites online, and they were both terrible; so I decided to make a new website, and dabbled in lots of different website-creating frameworks. Eventually, I came to the conclusion of: why would I use someone else’s framework for something that is trying to demonstrate my feelings about who I am as a creator? I wouldn’t invite someone to a pirate themed birthday party on a flower invitation. -laughs- So I decided to make this website by learning how to code. Which means that some of the pages are really fiddly and badly coded… I showed a bit to someone, and he looked at it and was like “why are you using code style that stopped being used in 2005?” -laughs- So I’ve ended up with a website that’s this weird, Frankenstein’s monster amalgam of things that I’ve put together, and videos and comments from moments throughout its creation. I think of it almost like performance art. I did a project where I used a bit of the website, and had people sending me voice note [responses], and made a game soundscape type thing.

It’s worth mentioning that I’m planning to completely redo my website. But I’ll keep what is currently there as legacy website”, and make another one. I want to make a slightly more “normal” looking one, so it doesn’t look like it’s some sort of old website from 2008. Where I am now, having made all of the website, I want to start again from a fresh point. I think currently, my website doesn’t look super approachable; I want to have other options, basically.

One question that’s stuck out to me is: how does structure fit into this? How do these ideas work on a more macro level?

I’ve touched a few times in this conversation on the things that we are told, as composers: how we are taught, what we are taught. And pacing is another one of these things. We’re sort of taught about pacing, we’re taught that pacing is important… Obviously, we’re not told “you must do this, it’s the (composing) law”, [but] a lot of the way music is talked about, these strict frameworks for pacing, for shape — structuring a piece — centre an idea of how an audience is listening. And who are we to assume how the audience is listening to something?

Of course. So how does that fit into your compositional process?

In this piece I wrote for three singers, violin, percussion, and tuba… that piece is about an aeroplane — well it’s not really about an aeroplane. Everyone says it’s about an aeroplane, because it’s got an aeroplane “bit”. But it’s also about other things. I just decided to sit down and write the whole of the text and go wherever I want to from there. [I] didn’t make a plan in advance. It was quite a key moment for me, in that often I think about pacing in terms of “how am I going to structure the whole thing”, rather than think about it in terms of “ok, what do I want to happen next?”

Actually, this is something I also picked up from NYO where you start by just sketching out a vague shape of the whole thing. For quite a long time, I was planning pieces like this; it meant that I was thinking really carefully about the broad brushstrokes, the overall shape of the piece. But I got to a point where I [was] almost unsatisfied by that; because I don’t think I listen to pieces like that, I don’t think I think of my own pieces like that, and I don’t think I think about my pieces like that when I’m listening through them. I just decided to not always do that, and try writing music as a stream-of-consciousness.

“You can put two things next to each other, and no matter how they’ve been conceived, they are going to connect to each other, and people are going to connect them.” Fraz Ireland, in conversation with PRXLUDES

Tweet

Do you feel like there was a point where you found a happy medium between these two ways of working?

For ‘…And mother said’… I literally went through it and was like “it’s gonna start with these horns, and I’m gonna have this massive piano-doing-the-same-chord-bit, and now [there’s] a saxophone solo” — so it’s like these chunks [of] different lengths. And it was a key moment for me, in that it was a time when I was like: I’m going to start writing music that is paced in a way that I would like to listen to music, and it is paced how I would like to be engaging with [music], rather than writing something that is paced in a way that I think the audience will understand. I’m not writing a piece of music so that someone who’s listening to it is gonna be like “Yeah, that was really cool. It got bigger, and bigger, then it got really small and quiet, and it got bigger and then it stopped.” And they understand it as an overall shape. I would much prefer someone to be like “Yeah, it was really fucking weird that there was a three minute piano solo in the middle of an orchestral piece.” I’m not trying to presuppose how an audience is going to be pacing themselves through my work.

So a bit after that, I realised that I had ADHD. I then started to go back a bit, and think about that in terms of pacing. How that has affected — and affects — the way I write, the way I think creatively, the way I engage to other peoples’ work as an audience. It got to a point where I realised that I had been trying to write music for an idea that I had, that I didn’t understand, of how I was being told other people were going to be listening to things. I was never convinced by the way I was pacing things, because it was never how I was listening to anything.

Of course. I totally empathise with that; realising how you and your perception of your art are necessarily intertwined.

I think that a lot of people approach pacing in the way that they do because [of] other people. I broadly think that all art with a temporal component is just about the curation of tension over time. You’re doing that in loads of different ways — whether with video, or sound, or dance — [but] by talking about the idea of curation of tension over time, we’re already assuming that an audience is gonna have a similar idea of what tension is, and a similar of understanding of that. It’s the same kind of question as: what if everyone’s seeing different colours? Does it matter if we are seeing different colours?

Should it matter? I guess if we’re all experiencing it, and talking about our experiences…

It comes down to this thing of: yes, we can’t presuppose, or second guess, what an audience is going to be experiencing, or how they’re going to experience it. But they are going to be taking in an experience from all of the stuff that’s happening. It’s not necessarily going to be based on this structure that begins with the first note of your piece, and ends with the last note of your piece, and is entirely about the sounds. We don’t do that; I don’t think people focus like that. I’ve been in so many concerts where I’ve found the music really interesting, but someone else who’s there also influences the way that I’m experiencing it. Or the pattern of the bricks on the walls. Whatever it is, these other things are affecting you.

Which brings us in a circle back to the score, and the title, and the programme notes. If I’m going to compose a piece which occupies 10 minutes of an audience member’s time, and I want them to engage with that [and] exist in that world for 10 minutes: why wouldn’t I do as much as I can to help make that happen? Whether that’s making the font in the programme notes the right kind of font for the vibe, or making the title something that’s very evocative. Give a little nudge into the right headspace. The same with the performers; so often, as composers, our players won’t have [so] much time to rehearse. That’s not the performers’ fault — it’s just the structure of the way everything’s happening at the moment. Why wouldn’t you do everything to help them make it as much of what you want it to be as they can?

–

More of Fraz’s work can be found at the links below:

- https://www.frazdotcom.com/ (interactive website)

- https://www.frazdotcom.com/normalsite.html (more “conventional” information)

- https://soundcloud.com/fireland

- https://vimeo.com/user96144444

References/Links:

- Fraz Ireland’s ‘Music for the Changing Hour’ concert, featuring music by Patrick Ellis, Rylan Gleave, and more (2021)

- ‘Napping before an exam is as good for your memory as cramming’, New Scientist (2016)

- Beethoven – Symphony No. 4, performed by hr-Sinfonieorchester in Frankfurt, 2016

- Fraz Ireland’s website survey

- Fraz Ireland’s views on Microsoft Paint

- Fraz Ireland, ‘4th ought sing raved ink loud’ (2021)